This article was originally published in the September 1980 issue of Inside Sports (CHRIST, anyone remember that magazine? I know Kralovec does) and appears here with permission.

Yes, I am a pirate,

Two hundred years too late.

The cannon’s don’t thunder,

There’s nothing to plunder…

Jimmy Buffett wrote the song, A Pirate Looks at Forty, in honor of a familiar character around the treasure-dreaming bars of Key West, where adventurers stare at wrinkled maps and empty shot glasses and wonder if they have finally run out of land.

But somehow the lyrics have always fit as comfortably as an aged T-shirt or a young blonde around the slightly bent shoulders of

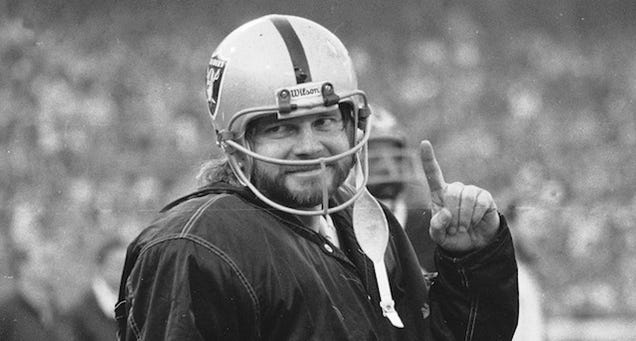

another regular at bars from California’s Left Coast to Alabama’s Gulf Coast. Once the swashbuckling air about Kenny (Snake) Stabler derived partly from the crossed swords and eye patch on his silver helmet and the pillaging demeanor of the black-clad Oakland Raiders. But this year the pale blue of his new Houston Oilers has not dimmed the piratical glint in his squinting eyes. And the vaguely wistful quality of Buffett’s song seems relevant. In the next few months, he will either lead the powerful Oilers to Super Bowl treasure—or show, as Oakland managing general partner Al Davis has suggested, that he has finally run out of land.

As the pirate looks at the age of 34, he claims he isn’t slowing down.

His headquarters now is Gilley’s in Pasadena, just outside Houston, where the shift workers from the oil and chemical plants still ride the mechanical bull and swill beer as if

Urban Cowboy had never threatened to commercialize the scene. Stabler and his good buddy, Killer the bouncer, are among the last holdouts against any incipient trendiness. “I’m settled down on the shit-kicking side of town,” he says. “You know it’s my kind of place when I can pretty much throw a quarter in any direction and punch up some country on the jukebox.”

The new hangout is much bigger, but not really very different from the other venues in the party that is Stabler’s life. The Gulf Gate or the Dirty Bird in Gulf Shores, Alabama. The Nineteenth Hole in Alameda. Working folks’ places where a guy can gamble on shuffleboard or pinball, hear loud music and drink according to his private notions of moderation.

“I know my limit,” says Stabler. “I’ve just never reach it. Or do you call throwing up reaching it?”

His motto is that of a man whose main worry in life is that he might miss something while driving between saloons.

When Stabler enters a bar he likes to yell, “Strike, lightning.” In one form or another, it often does.

On the football field, this is a quarterback who, after a rough sack, has wiped blood from his gray beard in the huddle, looked up at the scoreboard and seen only blurred lights, and told his teammates, “It feels like an awful bad hangover. Luckily, I’ve had some practice. Let’s go.”

“Kenny lets you know that he’ll do what it takes if you will,” Oakland’s All-Pro guard Gene Upshaw once said. “If it’s third and 20 and he’s banged up, we know he’s not going to throw some half-assed screen pass and wait for us to punt. If he needs extra time, he’ll ask. And we’ll bust ass to give it to him. Nobody wants to go back into that huddle knowing his guy nailed Kenny.” His leadership helped the Raiders into five straight AFC championship games and a 1977 Super Bowl rout of Minnesota.

Then it turned sour in Oakland. The last two seasons produced 9-7 records, disasters by Raider standards. While Stabler was throwing 30 interceptions in 1978, Al Davis became critical. “We had a lot of breakdowns and Kenny was just one them,” Davis says now. “He wasn’t terrible. But he was like a baseball pitcher who goes from a 25-4 season to maybe an 18-7.” In retrospect, this sounds like a fair enough assessment. But at the time, it came out this way: “The quarterback makes the most money, so he should take the heat.”

Strangely, the quarterback who never gave a damn what people said was hurt by the words. He had never been close to Davis, but reacted as if a father-figure had turned on him. Once known for his cooperation with the press, he stopped speaking to most reporters. He also ceased communications with Davis—except when demanding to be traded. Davis, in turn, let it be known that there was not a booming market for an aging passer with bad knees and unconventional conditioning habits. Finally, another top quarterback became disconnected with his own club—Dan Pastorini in Houston. Davis made the trade. But just to spoil Stabler’s delight at moving to a country-music area near his Alabama home, Davis called Stabler’s friend and attorney Henry Pitts, and said, “Sorry, Henry. The deals’ off. He’s going to Green Bay.”

On the football field, this is a quarterback who, after a rough sack, has wiped blood from his gray beard in the huddle, looked up at the scoreboard and seen only blurred lights, and told his teammates, “It feels like an awful bad hangover. Luckily, I’ve had some practice. Let’s go.”

“He’s changed his mind,” retorted Pitts. “He wants to die a Raider, Al. I hear that when somebody tells you that, it’s an automatic raise for him.”

Beyond the edgy humor of departure, the party line in both Houston and Oakland is that this will be one of those good-for-both-clubs deals that owners seldom achieve. Stabler’s unquestionably accurate left arm could be a perfect counterpoint to the running of Earl Campbell. Pastorini, three years younger than Stabler, buys time while the Raiders develop future quarterbacks like the rookie Marc Wilson. He may also provide the long ball that Davis says has disappeared from the Stabler-directed offense.

But the optimistic claims lead to nagging questions about Stabler. Has the crafty Davis unloaded a Hall of Famer when the toll of reading all those game plans by the jukebox lights is showing? Will the battered knees stand up through a season playing primarily on artificial turf?

John Madden, a great admirer of Stabler who coached the Raiders until a year ago, offers an interesting answer: “Al always believed in getting rid of a guy before he has pissed the very last drop. But Kenny’s like Bobby Layne or Bill Kilmer. Even if he has lost a little arm strength, he’ll find other ways to piss on you.”

“All I know,” says Stabler, “is that I’m 34 and raising as much hell as ever, and last year I was second in the conference in passing. The rest is all bullshit.

I don’t have to argue about what I can still do. I just want somebody to say, ‘Here’s your receivers, here’s your fullback, let’s get on with it.’”

That happens to be roughly the coaching method of Houston’s Bum Phillips. A country slicker who can match X’s and O’s with anybody, Phillips prefers to hide the technical stuff behind his cowboy hat, fancy boots and “Godalmighty” shrugs.

“On a real hot day of practice,” Stabler says, “Bum will take off his hat and wipe his forehead and say, ‘Come on, guys, let’s go drink some beer.’” Houston’s amazing upset of San Diego in last year’s playoffs was probably the quintessential distillation of the Phillips style. On the sidelines, his staff stole the Chargers’ signs and completely outsmarted the rival coaches. And on the field, Phillips’ players reached down for the courage and character to win without their two stars, Pastorini and Campbell.

Phillips and Stabler walk off the field after a loss to the Raiders. Photo via AP.

Now Phillips is approaching Stabler in similar fashion. The two have had many long sessions, trying to incorporate the most effective features of both the Houston and Oakland passing attacks. For public consumption, Phillips offers the straightforward lines Stabler likes: “I reckon that if will take Kenny about fifteen minutes to learn our system.”

As his boys’ summer football camp in Marion, near Pitts’s home in Selma,

Stabler was fast and glib with visitors who asked about the tales of his carousing. “They’re all true, unless you know some I haven’t heard.”

But moments later, he could be found in a huddle with Skeebo Whitcomb, the good old coach of the Selma High School Saints and the director of the camp.

Skeebo wanted details about the patterns that freed tight end Dave Casper over the middle. Stabler explained in detail, then explained again to a couple of his campers. Then he ran some sweaty plays with the kids, oblivious to the fact that three of his favorite things—beer and air conditioning and a shapely young blonde—awaited a few hundred yards away.

This is not meant to imply that beneath the fast-living image, there lurks the scholarly soul of a playbook librarian. For that matter, the scene may have been played partly for the benefit of a local TV crew.

But it is a reminder that there is more to Stabler than his own self-description of “big pickup trucks, fat belt buckles and a few laughs.”

He did not become perhaps the most accurate passer in history merely by standing grittily in a pocket an aiming in the general direction of Fred Bilentnikoff’s stickum-smothered body. He studies his business thoroughly. And for all his gestures of uncaring swagger, he loves it enough to play it for fun with a bunch of kids.

Some people will always be offended by the pursuit of small pleasures. But others will react with curiosity: Can a master of his profession really be this childlike, this fun-loving, this free of deep or introspective concerns? The answer, as near as can be gleaned over several years in several places, is yes. Not that there is no contemplation. In particular, Stabler tends to reflect on his mortality as an athlete. But even that comes back to a justification of the onrushing lifestyle.

I have been drunk now for

Over two weeks…

Now I’m down to rock

Bottom again,

With just a few friends

Just a few friends…

Stabler was not drunk this summer in Alabama. He was reaching into a cooler and making sure that he and his friends had enough to drink. Otis Sistrunk, the former Raider defensive tackle with the demeanor of a black mandarin executioner, was in town. So were Kenny Burrough, Stabler’s new deep receiving threat in Houston, and Ronnie Coleman, and Oiler halfback. Russel Erxleben, the great Texas kicker now with New Orleans, was also there to work at the camp. And when the subject of Stabler’s interceptions was broached, Kenny contemplated the roll call: “When you hear the word ‘interception,’ you know there’s a writer around.”

Henry Pitts was choreographing the evening. So his first duty was to pull off the road from Marion to Selma and head into a grocery store. “Y’all want some beer for the trip?” Pitts called. The trip was to take at least 20 minutes.

Properly fortified, the group raced into Selma, where they visited Pitts’s house and drank some more beer. Then, with no real explanation, the group was off to a predominantly black social club in Selma. There were several rounds and some curious glances before it became apparent that the group was on a political mission. Pitts’s friend, Joe T. Smitherman, was running to regain his job as mayor. He had resigned in July of 1979 for personal reasons. But he figured he could get it back with some classic New South campaigning, including an appearance with an interracial group of football stars.

“I’m the one man who understands Southern politics,” Smitherman was soon telling the group. “As mayor, I ordered the arrest of Martin Luther King down here. I said, ‘Dr. King, don’t march.’ And he marched. So I had him arrested. And got 70 percent of the black vote in my next election. What you Yankees have to understand is that we’re not segregationists anymore. We’re populists.” A couple of the blacks fidgeted. Stabler rolled his eyes and muttered, “Henry’s done it again.”

The speeches were not an unqualified success. The audience cheered politely for the ballplayers, but fell ominously silent when Pitts tried an oratorical flourish of, “We in Selma have not merely overcome. We have conquered.” When Sistrunk followed at the mic, he was barely audible. “Speak up, we can’t year you,” somebody called. Sistrunk stared balefully across the room. “If you can’t hear me,” he said, “you can move in closer.” A chair squeaked and there were a few nervous giggles. Stabler said a few words himself but watched most of the proceedings from the bar. “A situation comedy,” he said.

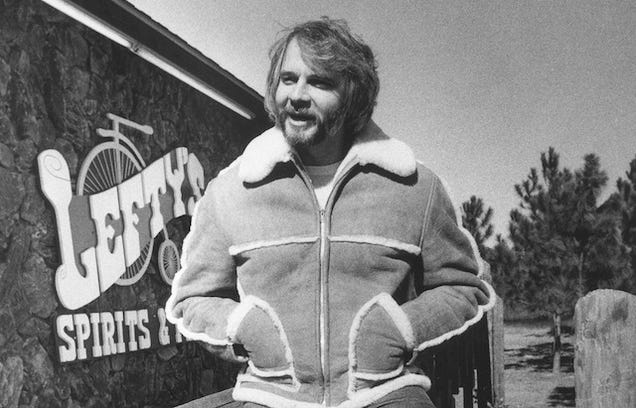

Stabler hanging out in front of a bar he owned. Photo via AP.

Undaunted, Pitts launched another round of speeches about his friend Smitherman, while the entourage guessed how many votes it was all winning for Joe T. The highest estimate was five. A few weeks later, the election indicated that Joe T. and Pitts really do know more about their politics than football players or writers: Smitherman won easily. By that time, Stabler and his friends had moved on—through a bunch of good steaks and then to Selma’s late night joint, Desperado’s.

One of the group drank two cognacs and ordered a third. “I don’t know who are you buddy,” said the bartender, “but you just drank all the cognac in Selma. Don’t get much call for that stuff around here.” Burrough warned against letting strange women get too affectionate: “I was sitting with a real fine lady one time, feeling mellow, and she kept softly stroking my arm. Before I realized what she was doing, she almost had my Rolex in her purse.” A woman passed out, and a member of the entourage broke his glasses while trying to pick her up and prop her on a chair. It was a slow night. Somewhere in the middle of it all, Stabler, smiling and satisfied, drove off at high speed with his girlfriend, Jackie Lones.

I go for younger women,

Live with several awhile,

Though I ramble away,

They come back one day,

Still could manage a smile.

Jackie Lones is a 24-year-old package of blonde beauty, unliberated philosophy and unabashed adulation for her twice-married lover. Born in Ohio, she met Stabler in Mobile a year ago and has lived him for most the days since. “I’m about the luckiest girl in the world,” she says. “Keep those cards and letters coming,” says Stabler. With his gray beard and long hair, he makes no effort to be fashionably or classically handsome in the mold of a Pastorini or a Namath. In fact, the friend who is shooting film for Stabler’s new TV show keeps begging him to get a haircut, “so Houstonians won’t think they traded handsome Dan for some aging faggot from California.”

But however he looks, Stabler has the blend of macho, wry humor and fame to attract the kind of companionship he wants.

“I wonder what it would be like to find a real liberated type,” he says. “Maybe she’d get a job and make so much money that I could quit getting my ass beat up every Sunday. But all the independent skill I really need in a woman is the ability to drive a pickup truck, so we can get home if I happen to pass out.” On the other hand, this does not mean that Stabler demands a homemaking servant: “As far as cooking goes, the only time I expect a seven-course dinner is when I hand a girl seven cans and an opener.”

Stabler’s best-known girlfriend of the past, Wanda Black, was a sterling example of that culinary school. Stabler once ruled the stove off limits to Wickedly Wonderful Wanda after she tried to heat up some TV dinners without removing them from their boxes. Wanda, “nice with a little spice,” was always a good foil for Stabler’s sense of humor.

“This boy has taken me from my simple Georgia home and corrupted my poor little innocent body,” Wanda once began a conversation.

“Yeah,” answered Stabler. “I took her right out of school. What did they call that university on Peachtree Street with the neon lights?”

Wanda, only eight years younger than Stabler, was once asked what she saw in him. “I got a grandfather fixation,” she replied quickly. When Stabler was asked recently why they broke up, it was half hoped that he would explain that she got too old. But his answer was more simple, and direct. “It just ended,” he said. “Like they all do.”

I’ve done a bit of smuggling,

Run my share of grass.

Made enough money to buy

Miami

But I pissed it away so fast.

Never meant to last,

Never meant to last.

“Making money has never been a big problem,” says Stabler, whose salary is $342,000. “Keeping it has sometimes been a different ballgame.”

Bear Bryant, who coached, counseled and suspended Stabler when he played at Alabama, often wondered whether Stabler would hold onto the money he would surely make as a pro. At this point it can be said with some certainty that Stabler will never be a conglomerate. His basic assets consist of a big house, a boat and a pickup—and a saloon called Lefty’s in Gulf Shores. He doesn’t figure that a country boy is meant to worry—as long as there’s always enough money to keep the nights alive.

“As far as cooking goes, the only time I expect a seven-course dinner is when I hand a girl seven cans and an opener.”

Stabler first met his attorney and partner Pitts in 1969, the year he took off from football. His post-operative knee had not responded to bar-stool physiotherapy, his first marriage was in trouble, and he suddenly quit Oakland and went home. His first wife was living in Selma, and he met Pitts while living there. “Kenny had a job selling Cotton State insurance,” recall Pitts. “As near as I could tell, he never opened his packet. I helped him get a radio show to tide him over, and I talked to the Raiders for him to arrange for him to go back.”

Pitts and Stabler have been together ever since. Perhaps their biggest coup was Stabler’s signing with the Birmingham team in the World Football League. Stabler signed for a three-year deal for a reported $350.00 in April of 1974—while agreeing to honor his contract with Oakland for the next two seasons. When Birmingham balked at a $30,000 payment Stabler was supposed to have received—but never did—in 1974, the Snake was released from his WFL contract. “We got some good money and Kenny never had to play for them because the WFL folded,” says Pitts. “But we walked out of there and left another 100 grand on the table, agreeing to take deferred payments that, of course, we never saw.” This statement qualifies Henry Pitts as a unique figure in sports agentry—a lawyer who will admit that he cost his client money.

“I can say it because we understand each other so well,” Pitts often says. “He’s the brother I never had.”

“Hey, Henry, speaking of business,” Stabler interjects just as often. “Whatever happened to that investment deal we made…”

“As I was saying, we’re like brothers. We don’t have to keep track of every detail.” Pitts opens a beer as deftly as he evades the question, takes a gulp and sighs blissfully. “In business you work is never done. You’re like a cowboy. Always something else to brand, lasso or ride.”

Off-the-field opportunities have increased tremendously for Stabler in Houston, where his country style gives him many natural endorsement tie-ins. He already has firm deals with a department store and for a television show. But all the arrangements smack less of boardrooms than of guys leaving large piles of change on the bar in a place where they know they can trust everybody. The less-than-hard-driving approach may help assemble the worst TV show in history—or one that turns the bend into the absurd and generates some rich unintentional comedy. Pitts figures that he will eventually throw together videotapes, instructional films and awards to high school players into a kind of Texas chili. If Houston doesn’t bite, the only certainty is that Stabler will be the last to get excited about it.

The deals with stores tend to be just as informal. “We went into one Western wear store,” recalls Pitts, “and the guy showed me a beautiful $300 pair of boots. I said, ‘My wife would kill me if I came home in a $300 pair of boots.’ The guy said, ‘Why? You’re paying us for em’.’ What a town.”

“At least,” says Stabler, “until the first time I throw three interceptions in a game.”

The only affair involving Stabler that brings no laughter, it seems, is the ugly incident after the 1978 season, when Sacramento writer Bob Padecky was set up for a cocaine bust in Gulf Shores. The circumstantial evidence against Stabler was considerable. Padecky was one of his least favorite writers, yet was invited to Stabler’s hometown for an exclusive interview. Coke was planted under the fender of his rented car and police were tipped off. Padecky unwittingly trivialized the incident a bit with his frenetic by-lined account of his harrowing jail term—which lasted five minutes before the cops realized it was a prank. But the fact remains that someone had executed a cruel and potentially dangerous stunt, and many observers felt that some of Stabler’s friends had participated—with or without his knowledge. When the subject is raised now, all the whimsical and piratical expressions dissolve into a look of abject innocence. “I just don’t know what happened,” he insists. “Maybe nobody ever will.”

When all his business affairs are shaken out, the chances are that Stabler will live out his days with all the hats and boots and fast boats he can use—and not too much surplus.

“Henry and I have always been better friends than partners,” says Stabler. “As long as we have enough cash around to keep running together, I guess we’ve worked out all right.”

Mother, mother ocean,

After all the years, I’ve found

Occupational hazard means

Occupations’ just not around…

Stabler’s first outing with the Oilers—a 21-7 exhibition game loss to Tampa Bay in the Astrodome—was a personal success. The Snake was 9-of-15 passing (with three “drops”) and guided the Oilers to their only score on an 81-yard drive in the second period. The mood among Oiler fans—48,827 of whom attended the game—was almost euphoric. Stabler was pleased by his performance, but cautious. “I’m no savior,” he said. “Who the hell is going to save a team that went 11-5 last year?” But he also admitted: “With Earl and good receivers to throw to, I imagine we can make defenses pretty nervous.”

Out in Oakland, there is reason to be cautious about superlatives. “Of course, Kenny uses all his receivers well,” says Al Davis. “He knew that was his best chance to stay effective. But the fact is he’s gradually gone from a deep, vertical game to a lateral one. We adjusted somewhat. But when we did, we settled for being merely respected instead of feared on offense. And my kind of offense must be feared for its knockout punch. I mean, grace and skill are fine. But if you had to choose, who would you rather fight, Leonard or Duran?”

Among long-time Raider followers, there are darker whispers. Some point out that since the Oilers have already gone to title games without him, they have acquired him largely to win such games. And it’s mentioned that in five straight championship games, from 1973-1977, the Raider offense generated just one first-half touchdown. Stabler’s supporters blame this on conservative game plans that didn’t allow him to cut loose until he was behind. His detractors say he grew tentative in the big ones. A few even claim that he has become even less aggressive in his waning years, and that he might be willing to earn his money on the bench before the year is out, watching young Gifford Nielsen take charge.

Then there is the most serious occupational hazard: the carpet. “It won’t bother me,” Stabler insists now. But over the years he has complained that the artificial turf makes sacks more painful and his knees more tender. A year ago, he had only four games on rugs. This season, he must endure 12 of those experiences. All the debate about his arm and his enthusiasm may become irrelevant if the turf takes too brutal a toll.

“You can’t avoid the fact that it will be a problem,” says Madden. “But Kenny’s got the right coach to help him handle it. Bum isn’t a by-the-book guy. If Kenny’s knees are hurting, which they will be each week after playing on artificial turf, Bum will be flexible enough to keep him out of practice for a few days. All he needs is one good workout on a Thursday anyway, and I suspect that’s all he’ll get. Under that routine, he could survive.”

On a more spiritual level, even Davis says that Stabler could rise up and enjoy a great season. “He’s grown a little stale mentally, but the trade could motivate him. Remember, we’re still talking about great talent, the most accurate passer who ever played the game. I have no ill will. I wish him the best. But remember one other thing. The guy who traded him away is the smartest guy in the game.” Davis laughed wildly, to make sure you know that he is joking. Maybe.

“The trouble with all this talk,” Stabler says in a quiet moment, “is that people are going to say, ‘Stabler got Houston past Pittsburgh,’ or ‘Stabler couldn’t cut it anymore.’ I resented it when Davis put the blame on me. Nuclear physics may be an ‘I’ game. But football is a ‘we’ game.”

But even as he talks, Stabler knowns that he will never enjoy that cool, sensible perspective. “I’ll take the heat if I have to, just like Davis said. I’ll never change my style because of what people write or say. Hell, when you bring up the time I threw seven interceptions in a game, I’ll look you in the eye and tell you that if the game had gone three more hours, I’d have thrown 15. I’m not going to stop trying to catch up just because somebody’s criticizing me.”

Stabler pauses and lifts up a sweating beer can to his curled lips. Jackie Lones places a hand on his arm, and smiles. “If we go all the way, I’ll own Houston,” he says. “If we go 9-7, I’ll be looking for a sheep ranch some place to get away from the abuse. But what the hell. How many guys ever get to face those possibilities?

Sure, you’re damn right I’ll take the heat. Or the Super Bowl ring.” Strike, lightning. The pirate is ready.

The Oilers went 11-5 that season and lost the wildcard game to the Raiders, 27-7. Oakland went on to win the Super Bowl, defeating the Eagles, 27-10.

Pete Axthelm graduated from Yale in three years and his senior thesis, The Modern Confessional Novel, was published. Axthelm was a turf writer at The New York Herald Tribune and briefly at Sports Illustrated before moving to Newsweek, where he covered a variety of sports and general interest topics. Later known as a TV personality at NBC and ESPN, he also wrote The City Game.